So enjoy this post; and I'll try to finish strong in Egypt with at least one more post after this and then a third wrap-up post.

Ghosts of the Sinai

Since I've been in C

airo, I've fallen in love with the Sinai Peninsula. I've been numerous times and can't get enough. In fact, I just returned from my last trip on Sunday. Except for once, when I went with my parents to Sharm el-Sheikh, I've been going to a little strip of coastline called Ras Shaitan, literally meaning "Head of the Devil." It's a stunning place on the east coast of the peninsula, just about half an hour from Israel. It sits on the Gulf of Aqaba. Especially incredible is how at night you can see the lights from Saudi Arabia, right across the Gulf, the lights from Jordan, slightly north, and the lights from Israel, at the northern tip. You sit on these empty beaches, watching the calm surf, the jagged mountains, and the odd passing camel, you realize why this is a land worth fighting for.

airo, I've fallen in love with the Sinai Peninsula. I've been numerous times and can't get enough. In fact, I just returned from my last trip on Sunday. Except for once, when I went with my parents to Sharm el-Sheikh, I've been going to a little strip of coastline called Ras Shaitan, literally meaning "Head of the Devil." It's a stunning place on the east coast of the peninsula, just about half an hour from Israel. It sits on the Gulf of Aqaba. Especially incredible is how at night you can see the lights from Saudi Arabia, right across the Gulf, the lights from Jordan, slightly north, and the lights from Israel, at the northern tip. You sit on these empty beaches, watching the calm surf, the jagged mountains, and the odd passing camel, you realize why this is a land worth fighting for.I first heard about the ghosts of Sinai came when we were planning a trip there a few weeks ago. I asked my friend Tom, who's working here in Cairo, if his driver Ahmed would drive us there. He told me that he usually gives Ahmed the weekend off when he goes to Sinai because Ahmed is terrified of the ghosts there. Asking around, I found out that Egyptian legend

has it that so much blood has been spilt on the land there that thousands of ghosts wander the peninsula and have been known to cause car wrecks there at night. Later, asking the Bedouins at the camp about the ghosts, they confirmed the myth. I've asked various people in Cairo, too, and found this to be a popularly held belief.

has it that so much blood has been spilt on the land there that thousands of ghosts wander the peninsula and have been known to cause car wrecks there at night. Later, asking the Bedouins at the camp about the ghosts, they confirmed the myth. I've asked various people in Cairo, too, and found this to be a popularly held belief.And then came our drive home from Ras Shaitan a few weeks ago. Driving back to Cairo involved driving straight east across the thick part of the peninsula, initially through about half an hour of coastal mountains followed by a four or five hour stretch of barren desert before reaching the tunnel under the Suez Canal.

We drove through the night, racing something of a night's sleep back in Cairo. It had been about an hour and a half since we'd seen our last town, or any form of civilization for that matter, when Tom got tired of driving and as

ked one of us to switch off with him. He pulled off the road, a precautionary but unnecessary step since we hardly ever passed any vehicles. As we all got out to switch seats, I looked across the road to see a turban-clad Bedouin man staring at us. Startled, we all rushed to hop back in the car. As I was hurrying, I said good evening to him in Arabic, to which he replied affably. As soon as all the doors to the car were shut, we raced off into the night, sure we'd pass a village over the next dune. Incredibly, we saw neither a house nor a village for another hour or two. Not only was this man hours driving from the

ked one of us to switch off with him. He pulled off the road, a precautionary but unnecessary step since we hardly ever passed any vehicles. As we all got out to switch seats, I looked across the road to see a turban-clad Bedouin man staring at us. Startled, we all rushed to hop back in the car. As I was hurrying, I said good evening to him in Arabic, to which he replied affably. As soon as all the doors to the car were shut, we raced off into the night, sure we'd pass a village over the next dune. Incredibly, we saw neither a house nor a village for another hour or two. Not only was this man hours driving from the  nearest shelter, he happened to be right where we pulled over our car! While that episode didn't convince me that ghosts exist on Sinai, it sure explained to me why 75 million Egyptians think they do.

nearest shelter, he happened to be right where we pulled over our car! While that episode didn't convince me that ghosts exist on Sinai, it sure explained to me why 75 million Egyptians think they do.Photos in this section (in order of appearace): The town of Dahab at sunset; Me at sunset on the road leading into the mountains; Ras Shaitan and the mountains behind it; Me on the shores of the Gulf of Aqaba with Saudi Arabia barely perceptible in the background.

Rip-Off!

As quick as Egyptians are to negotiate a good deal for themselves, they're just as quick and true in their honesty. Hand an Egyptian a 50 pound bill instead of a 50 piastre bill, they'll quickly point out your error and save you 49 and a half pounds. They'll play hardball when it comes to negotiations, but they'll always display incredible integrity when it comes down to it. I mean it: there's a heightened level of integrity here which is truly compelling. But with every rule, there are exceptions, and two weeks ago illustrated that honesty is never a universal virtue.

Coming home from classes at the end of the day, I did as normally would by hailing a taxi and told the driver my location. About two minutes into the ride, I got the typical question, "How much." You should know that Cairo taxis do not run on meters and that the prices are all about negotiations. I told him five pounds, about right for the distance. Later, we ran into incredible traffic and the driver, who was about my age, told me that five wouldn't be enough. I agreed because it's customary to pay more for trafficky rides. But I told him I only had a five pound bill and a one hundred pound bill. He told me that this wasn't a problem, to give him the one-hundred and he'd make change. He pulled out his money, and I handed him the hundred and he gave me back forty two! When I gave him a quizzical look he shot back, "You give me fifty, I give you 100." Furious, I demanded he give me a fifty. He coyly refused holding, a fifty pound bill at arms length. When I reached for it, he held it further away still. I tried again to take the money, but he wouldn't let me have it.

Sitting here writing this story, there's no good way to end it other than to tell you that we both left that taxi a little bruised (just shoving, no punching) but triumphantly holding my fifty pound note. It was only after I'd gotten out angrily that I realized I was in the middle of a bridge over the Nile with no sidewalk! It made for an interesting walk home through all the cars, and since the traffic was going about the same speed I was walking, the driver had plenty of opportunities to smirk at me from the comfort of his car. I merely waved the fifty pound note at him and smiled broadly.

Suckered by a Glass of Tea

While I'm on the subject of getting angry, I might as well tell you another story. Last week, during a five minute break in the middle of my three hour morning traditional Arabic class, I ran to the corner, as I had done so many times before, to take money out of an ATM. I used the Bank of Alexandria machine, and inserted my card. As soon as I gave it my card, the machine flashed a "Please remove your card" display, followed immediately by "Please insert your card." Just like that, my bank card was gone. My only means of cash had disappeared. Frantically, I asked the men who were sitting nearby where the Bank of Alexandria was located. One of them looked at me in bewilderment and said, "You used that machine? Why? That's an antique!" I could only roll my eyes and set off in search of the bank.

After being sent on a wild goose chase by would-be helpful policemen and doormen, I found the bank about half an hour later. I walked into the bank and told them my problem. At first they denied that they even had an ATM machine on the street I told them. After a while of negotiating, I finally obtained that admission from them. Just as quickly they insisted that there was nothing they could do, and that the confiscation of my card had been my fault for not keeping enough money in my account (I have plenty of money in my account). At this point, I flew off the handle. These people were clearly more interested in covering their own behinds than helping me get my card back. After making enough of a stink, they told me, of course, that they'd see what they could do. They told me not to bother waiting around and that they'd call me. I left and went back to class, having missed the almost the entire second half. I was steamed and more than a little nervous.

As my afternoon class began, I warned the teacher that I might have to take a call in the middle. Because it's a one-on-one, he had no problem with this. Sure enough, one hour into the two hour class, my phone rang. I answered the phone, and the woman from the bank told me I had to be at the bank in ten minutes. I asked her if I could be there in an hour. She told me, no, that it was absolutely critical that I be at the bank in exactly ten minutes or I'd likely miss my chance at getting the card back. So I apologized to the teacher and ran from school, sprinting all the way to the bank.

I arrived flustered and out of breath and asked them for my card. Sit down, they told me, it would come soon. Annoyed I took a seat and waited. And waited. And waited. About twenty minutes later, the rage in me had come to a boil. I had cut a class an hour short to make it there when they said, and they weren't doing a thing to help me. As I had really avoided doing for five and a half months in Cairo, I started yelling. I mean really yelling. It was civil, at least, but I took full advantage of the big vocal cords I have. In the middle of my rant, the bank manager looked at me and interrupted by saying, "Tea?" I stammered. "What?" I hissed. "Tea?" he repeated. I just started yelling again, "What the hell are you offering tea to me for? I just want my damn card back!" As I kept going, he gently picked up the phone and said quietly, "Lazim shay dilwaqti." We need tea now. Ignoring him, I kept on going until he interrupted, saying, "Sugar?" I just ignored him and kept howling. "Ziada," he said into the receiver. Lots of sugar. Two minutes later, an ancient little man rounded the corner with a glass of tea and pushed it into my stomach. I was obliged to take it. He then put an arm on my shoulder and gently guided me back into my seat. Before I knew it, I was drinking delicious Egyptian tea, quiet as a mouse, content with sipping the sweet tea he'd given me. Ten minutes later, my card came to me. I never said another peep.

It's hard to do justice in describing how they defused the situation, but tea is such a typically Egyptian way of dealing with a "situation" and the hospitality was so overwhelming, and the notion was so strong that you can't accept a gift from someone else and then still have them be your enemy, that I lost the rage immediately.

Back Handed Compliment

Like I told you, we went to Sinai this past weekend. I couldn't drive out there on Wednesday, when my friends went in a private car because I had class on Thursday, so I had to buy a bus ticket. My roommate Sam and I headed out to the bus terminal a few days before we wanted to leave, walked up to the window and inquired about bus times. I told the man that I wanted a 10:15pm ticket on "yom il-guma." Friday. The man took our money and printed out our tickets, and then Sam turned to me with alarm and said, "Theo, we want Thursday. You said Friday!" So in a flurry of flustered Arabic I apologized and told him that we need tickets for a day earlier. The man behind the desk went absolutely ballistic. He told me that it was "mish mumkin." Not possible. I told him, in somewhat of a white lie, that I get my days of the weeks confused in Arabic. He shot back that I should have just spoken English to him, to which I responded somewhat heatedly that I had come to Egypt to work on my Arabic.

He continued to yell for a while before heading out of sight to talk to his supervisor. He came back five minutes later with new tickets in hand, but was not going to let us get away without chewing me out a bit more. After a while, a well-dressed man behind us said to the man in Arabic that he should give me a break because I'm not that good at Arabic. And then came the moment of glory. The man behind the desk retorted that I spoke Arabic very well and that I understood everything and that language wasn't a valid excuse because of this. Hearing this, I got a proud smile on my face, and when he turned to give us our tickets, he was more than a little flustered that the kid he'd just yelled at for five minutes was grinning so broadly. Needless to say, that feeling of accomplishment stuck with me for most of the day. The daily struggles to master the language are all worthwhile just for those brief moments of unrestrained joy. It's too bad that sometimes the great moments come in the form of a good raking over the coals.

First Rain

In case you didn't know, it almost never rains in Cairo. On top of that, the rain is limited to December through February. My hopes of seeing a Cairo rain storm before I returned home were rewarded two weeks ago. Sitting in my apartment after dark a couple weeks ago, I heard an unfamiliar pitter-patter outside. At first I didn't register what was going on, but soon enough the magnitude of what was going on outside hit me. Cairo's first rain of the season.

I didn't even bother going to the window; I just grabbed my keys and sprinted to the elevator. I was horrified that the rain might stop before I made it outside. To my great relief, I landed on the sidewalk with a decent steady rain falling from the heavens. It was just the kind of rain that's decent and steady, but not one that would necessarily make you want to cover yourself. I stood outside very comfortably with no coat and no umbrella. That was me. The scene around me, by contrast, was utter chaos. Egyptians everywhere, running, sprinting, desperately covering their heads, heading for the nearest shelter. I laughed heartily as the frenzied scene unfolded around me.

The rain lasted only half an hour, and the city took about three days to drain. The only remarkable thing about the rainstorm came after I had been outside for about ten minutes and was ready to head in. As I turned to head back to the apartment, I felt my lips begin to tingle. After a minute, the tingling rose to the level of a dull throbbing. It never got any worse than that, but it was in that moment that I realized that we were being treated to an acid rain storm. I assume that the source of the rain is the Nile which, up and down, from Aswan to Alexandria, is immensely polluted. It was then that I realized that there was probably more sense in running for cover than I had initially imagined.

Basha

Let me take you back to the first day of Ramadan. Excited by what promised to be an exciting month, I decided to try fasting for a day or two just to see what it was like. I figured that as an aspiring Middle East historian, I should try to understand the culture of Ramadan by experiencing the fasting first-hand. I resolved only to fast for a day or two since I'm not Muslim and do not feel the spiritual element that carries so many Muslims through the month.

On the first day of Ramadan, I made the critical mistake of not getting up for the pre-dawn meal. I got up at eight, went to classes at nine, and came home by two in the afternoon. What makes the fasting so difficult isn't that you can't eat. What makes it so tough is that you're forbidden to drink. It was still very hot in Cairo, and by the time I came home from classes, I was dying for a glass of water. I'm lucky that I'm not a smoker because I can only imagine how tough going without nicotine all day must be.

By about three in the afternoon, I was not a happy camper. I was sitting on the sofa not doing anything, and so my mind lingered on my hunger. With a good deal of resolve, I stood up and went down to the big supermarket in the basement of my building. I decided that I'd spend the last two hours before the break-fast buying a cooking food. I smiled to myself because I wanted to make something tasty, but in my four months in Cairo I had only mastered the art of spaghetti and tomato sauce. Several other failed cooking adventures over the months persuaded me to stick to my one dish. On the first day of Ramadan, however, I knew things would be different. I bought sausages, egg plants, tomatoes, rice (the proper cooking of which still remains elusive to me), and a variety of other foods. I headed upstairs very pleased with myself and began to prepare the meal.

It was about five minutes into my little adventure that a terrible thing happened. I was standing in front of the stove trying to light it when a giant New York City sized rat ran across my foot and under the stove. I jumped about thirty feet in the air yelling to the high heavens. I ran from the kitchen and tried to catch my breath in the living room. I didn't know what to do since I didn't want to be in the kitchen, but at the same time I had lots of food ready to be cooked and a belly that was grumbling. I'll cut the rest of the story short, except to say that it was quite an experience cooking an entire meal while standing on two dining room chairs, leaping from one to the other to move items from the refrigerator to the cutting board to the stove. And as for how the food itself turned out, let me just say that spaghetti and tomato sauce remains, to this day, the only dish I can cook.

Over the next week, the rats, yes two rats, made frequent appearance. While they stayed in the kitchen, they would run across the floor right as I, or my roommate Sam, went in there to get something. After a little while, we decided we need to do something. The problem was that because there are so many stray cats in the city, there are hardly any rats or mice to speak of. Consequently, stores don't carry mouse traps. After a week of searching, we were desperate. Finally, one night, when a big group of friends had gathered at our house, we asked for advice. After about half an hour of discussion, we decided what we needed to do: find a cat.

That night, we spent some time trying, unsuccessfully to catch a stray. The very next day, we headed to Giza, southwest of Cairo, to a pet store that my friend, Tom, knew. The pet store had only three cats. Two of them looked on the verge of dying of some terrible eye disease. The third one, however, looked healthy and strong. The assembled group discussed the cat for a while, and after a quick bit of negotiating on the price, we walked out with her.

When we got home, a raucous debate ensued as to what to name her. Finally we settled on Basha, the title given to pre-Nasser nobility and a term still used by the lower classes when addressing the more affluent (my doorman, for example, always calls me Basha).

Basha has turned out to be the perfect cat; she's sweet and playful by day, and she's a savage hunter by night. She wasn't always that way. One day, about a week after we'd bought her, Basha had followed me into the kitchen when the rat ran through. Basha took one look at that thing and ran into the corner of my bedroom where she hid for most of the night. But

then she got her sea legs. When our handy-man was doing work on our kitchen sink a week, or so, later, he came out and announced that he'd found a dead rat right by one of the little holes that they normally get into the apartment through. So not only had Basha killed the rat, but she'd left the rat right by the hole as a message to the others. Needless to say, we have neither seen nor heard from the rats since. Since the disappearance of the rats, Basha has adopted with ease her role as a peace-time pet. She's up every morning to greet me, sitting patiently on my bed everyday as I get ready for school. While she sleeps most of her afternoons away, she comes alive at around ten at night and leaps from chair to chair in the living room until I go to bed. She proved to be a little mischievous, however, one day when I was making popcorn. I was working at my computer when I got up to go take the popcorn of the stove. When I returned, I was shocked to find that my "t" key had been nabbed! I looked all over for it: under the sofa, in her food bowl (where she likes to keep little knick-knacks she finds around the apartment), and in my bedroom. It never turned up. I've since had to make due by prying the "]" key off and putting it in the "t" spot.

then she got her sea legs. When our handy-man was doing work on our kitchen sink a week, or so, later, he came out and announced that he'd found a dead rat right by one of the little holes that they normally get into the apartment through. So not only had Basha killed the rat, but she'd left the rat right by the hole as a message to the others. Needless to say, we have neither seen nor heard from the rats since. Since the disappearance of the rats, Basha has adopted with ease her role as a peace-time pet. She's up every morning to greet me, sitting patiently on my bed everyday as I get ready for school. While she sleeps most of her afternoons away, she comes alive at around ten at night and leaps from chair to chair in the living room until I go to bed. She proved to be a little mischievous, however, one day when I was making popcorn. I was working at my computer when I got up to go take the popcorn of the stove. When I returned, I was shocked to find that my "t" key had been nabbed! I looked all over for it: under the sofa, in her food bowl (where she likes to keep little knick-knacks she finds around the apartment), and in my bedroom. It never turned up. I've since had to make due by prying the "]" key off and putting it in the "t" spot.When I leave for the States later this week, my friend Moustafa will adopt Basha.

Three Legged Camels

I'd always heard about the camel market. Just outside of Cairo, it was supposed to be quite the spectacle. I had tried to go a couple times, but various things had intervened and prevented me from making it there. One day, my roommate Sam and I resolved to make it there no matter what the circumstances. The difficulty was that it only happened on Friday mornings and it began at six in the morning and all but finished by noon.

That morning, just a couple weeks ago, we got up around six and made it out the door twenty minutes later. Friday is a weekend day in Cairo, and there were almost no cars and no people on the road when we headed out. Because of this, we had several taxi drivers vying for our business. We ended up going with the one who spoke the best English and offered us the best price. We laughed all the

way because, not knowing we spoke Arabic, had double crossed some of the other cabbies, using his bilingualism to his advantage.

way because, not knowing we spoke Arabic, had double crossed some of the other cabbies, using his bilingualism to his advantage.The market was in the town of Ballish, just north and west of Cairo. Because of the open roads, we flew out of the city and were quickly driving through miles of farm land, punctuated periodically by squallorous villages. After about forty five minutes, we made it to Ballish. Asking for directions there, we found that the market was a good deal outside of town. It was a tricky journey out there that required a lot of turns down progressively smaller roads. But with each person we asked for directions, it became clear that we were fast approaching our destination. What let us know that we were almost there was a giant dead camel rotting by the side of the road. Before long, we rounded a corner and saw the expanse of the market ahead of us. After giving a couple pounds to mollify a man who demanded that we buy admission tickets, we began to navigate our way.

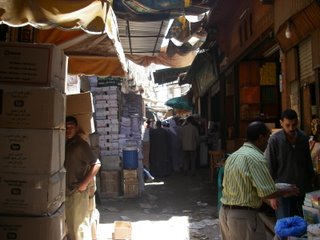

Let me describe for you the location first. On a vast expanse of dirt, two rows of ramshackle huts had been built about forty yards apart from one another creating a sort of road between them. All the business was done here. Breaks in the huts gave entrance to small side "courtyards," for lack of a better word, that also had camels.

There is one visual element that initially strikes a visitor. Most of the camels have one of their front legs folded up and tied at the knee joint. This makes it harder for the camels to run away, and astounded me as I looked out across a sea of seemingly three legged animals. The market has literally thousands of camels that have been driven north from Sudan across the desert to Cairo. Each herder has his spot on the road with between ten and fifty camels that he has either standing or sitting.

Sam and I walked down the road, surrounded on all sides by camels, trying to take it all in. One striking element of the market is the brutality with which the herders treat their animals. They all have three foot long sticks and slam their camels relentlessly with them. There's a difference between hitting a camel harder than a Westerner would like to see in order to get the camel moving from spot to another, and hitting a stationary camel repeatedly with no apparent motive.

One of the really incredible sights was witnessing the auctions. When a large enough group of people became interested in a camel, the owner would urge it away from the herd and his assistants would begin hitting it from all sides to show off its dexterity as it hobbled around. The owner would then hold court, animatedly trying to drive up the price. Understanding Arabic, it was fascinating for me to hear his tactics and listen as the price surged upwards. Twice we saw, at the conclusion of the auction, two men begin punching and shoving each other, an event that quickly escalated as men took sides and began swinging. Eventually the brawls would die out and the men would move on.

Like I mentioned, the camels are literally everywhere. At one point, Sam and I were standing on the road looking at some camels when I heard something behind me. I turned around to see an entire herd racing towards us. I had almost spotter them too late, but Sam and I ran (it was not easy to figure out where since camels were all over the place) and found refuge in a pack of lying-down camels.

Later, we found that one of the huts in the middle of the market was serving tea and shisha. The men at the market were shocked to see us come in, sit down, and order up a shisha. While we were sitting in the hut our driver appeared, as he had a couple times already, looking concerned and asking whether we were alright. He could not believe that we had wanted to come out to the market to begin with, and w

as constantly worried that the two white boys would be eaten up by this rough and tumble place. In the hut, we began talking to a little boy, probably thirteen years old, who was presumably the son of one of the herders. We asked him which were the best camels at the market, and at the end of our shisha he took us to one of the small side court yards and revealed to us a small herd of snowy white camels, well-fed and healthy looking. The owner looked like a king as he auctioned off one of his prized animals. No brawls here.

as constantly worried that the two white boys would be eaten up by this rough and tumble place. In the hut, we began talking to a little boy, probably thirteen years old, who was presumably the son of one of the herders. We asked him which were the best camels at the market, and at the end of our shisha he took us to one of the small side court yards and revealed to us a small herd of snowy white camels, well-fed and healthy looking. The owner looked like a king as he auctioned off one of his prized animals. No brawls here.After this, we headed back to the car, passing by a dog that was dragging himself by his front legs, which happened to be his only two, just to punctuate the destitution of the market. On the way home, I had an interesting language issue in one of the villages. I asked the driver to pull over at a sweet potato vendor to pick up some breakfast. The man, waiting in front of his donkey-drawn stand, looked as though he had never seen a white person before. And there's a good chance he hadn't. I walked up and asked him how he was doing and then asked for two sweet potatoes. As he had his back to me preparing the food, I tried to make conversation by asking him how his donkey was doing, "Izzay homarak?" He wheeled around with a look of fury before calming down and answering when he saw me pointing to his steed. I was a bit surprised by his initial anger and asked my friend Moustafa about it later. Moustafa doubled over in laughter, explaining to me that to ask "How's your donkey?" is an expression that essentially means, "You're an idiot." Still so much to learn….